I got a great email from a shooter yesterday asking me why I liked the isosceles stance instead of the Weaver stance.

In the isosceles stance, the shooter’s face, shoulders, hips, and feet are squared up to the target and the arms are outstretched, making an equilateral triangle with the arms and chest…like an arrowhead…that’s pointed to the intended target.

In the Weaver stance, the support side is forward, from shoulder to hip to foot which causes the support side arm to be bent much more than the shooting side arm.

Ironically, even though several instructors who I respect and admire use one of those techniques, I don’t use or teach either for self-defense, and I don’t often suggest that people change their stance because of the fact that there are almost always higher payback changes that can be made…like switching the majority of a shooter’s training time to shooting from a “non-stance.”

I do use Weaver for shooting big bore revolvers, because it causes the gun to recoil away from my face rather than towards it.

Now, if I were to pick a stance for static, straight ahead shooting, it would depend on the context and the gun I was shooting. If I was doing slow-fire precision pistol with a heavy gun/light trigger, it would be all about minimizing the wobble and finding my natural point of aim.

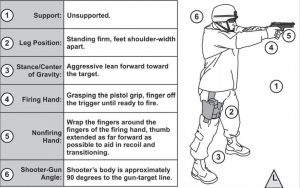

If I was shooting a lighter self-defense gun with a stock trigger, my stance would be similar to the “modified isosceles” or “combat” stances where the upper body is squared up to the threat/target and the feet are slightly wider than shoulder width apart, weight is dropped a little, and the support foot is in front of the shooting side foot…pretty much the same stance I’d use to punch a punching bag or push a bookshelf over.

But…and this is a big but…if you’re training for self-defense, you really want to move beyond a “perfect” stance to a “non-stance.”

In fact, the more perfect your stance is, the more it might bite you in the butt in a chaotic, real-world shooting situation where you need to engage a target at an other-than-perfect angle. The US Army FM-3-23.35 “Combat Training with Pistols M9 and M11” describes it as “adapting his shooting stance to available cover” and you absolutely MUST practice this to be able to perform at a high level when lives are on the line.

If all of your training is squared up to the target with a perfect stance, then it’s going to be incredibly difficult to figure out how to adapt that stance on the fly in a high stress situation.

Figuring things out, on the fly, under extreme stress, can introduce big drops in performance and incredibly long lags into the time it takes to get things done.

And, if we need perfect technique in order to make solid hits, then our technique is fragile and more prone to failure in real-world conditions.

If the shooting sequence in our brain that we take for every single shot in practice includes paying attention to our stance, then our default script under stress will be to also pay attention to our stance.

So, how do we “anti-fragile” our technique…make it more resilient?

In short, we’ve got to train with bad stances…in fact, we want to spend more practice time making good hits with bad stances than we do with perfect stances.

This is more challenging than most shooters realize.

Do it incorrectly…the way most do…and it can be overwhelming and hurt your skill level.

But, when you do it the right way, you’ll actually gain skill faster and easier than if you always used a perfect stance.

I’m covering the process tonight on our Dynamic Gunfighter presentation >HERE<

!Warning! If you’re not using the process that I share during this presentation, it means you’re spending more time, ammo, and money to develop skills than you should be.

The system I’m going to share will help you accomplish more in less time and for less cost than what is possible with any other live fire or traditional dry fire training tool or system you may be using, so check it out tonight by clicking >HERE<

Leave A Response